- Academic Acceleration of Gifted Students: Does it Work?

- Recent Articles List

- Make a Twist: Curriculum Differentiation for Gifted Students

- Gifted Awareness Week

- Aren’t all children gifted and talented?

Children learn and develop at different speeds, have different learning patterns and achieve at different rates. Those who achieve developmental milestones ahead of others at a similar chronological age are considered advanced in their development. Children who learn rapidly and grasp concepts more easily than others of their age are cognitively advanced or accelerated learners. Despite these differences, a child’s date of birth is generally used to determine when a child can enter formal education; so children who have significantly different rates of learning are placed together in school, according to their chronological age.

This results in children with a wide range of abilities and skills being placed together in classes as students are not usually placed in year levels according to their stage of development, learning abilities or academic skills. Teachers can use ability grouping to allow students with similar levels of academic skills to benefit from learning together. This strategy works very well for most students; however some very capable students have the ability to learn beyond the level that the rest of the students in their class are learning.

For students to remain engaged in school they must learn at a pace and level that is well matched to their intellectual abilities and academic needs. Some students are already beyond the curriculum for that year level and they need opportunities to learn with students who are currently learning at a similar level. Gifted students have the ability to learn at an accelerated pace and need exposure to more advanced curriculum. Some of these students should be considered for one of the many forms of academic acceleration, including subject and year level acceleration.

A faster pace of learning allows time for deeper exploration

Schools are becoming aware of extensive research that supports the use of academic acceleration as one of the most effective ways of providing for the intellectual, academic, social and emotional needs of gifted students. Research on the various forms of acceleration is rich and consistent in its reporting of very positive academic effects, and positive, but moderate to low effects, for socialisation and self-esteem (Rogers, 1991; 2002; 2004; Lubinski, 2004; Olzewski-Kubilis, 2004; Brodi, Muratori & Stanley, 2004). Despite this research, there is still much hesitancy about accelerating students.

For more than 23 years, Mirica Gross’ longitudinal study of 60 exceptionally cognitively talented young people documented the beneficial short-term and long-term effects of acceleration, both academically and socially. Gross’ study also found that those exceptionally cognitively talented individuals who had NOT been accelerated by at least one year were:

The Gifted Education Research, Resource and Information Centre (GERRIC) | School of Education | University of New South Wales presents research on attitudes that block or assist the implementation of school policies on academic acceleration.

Releasing the Brakes for High-Ability Learners

Overall the study’s quantitative findings indicate a general pattern of enthusiasm for acceleration tempered by key reservations on some issues. The qualitative findings confirm this and indicate that teachers continue to have concerns about social-emotional outcomes of acceleration and that social-emotional maturity tends to be defined subjectively based on teacher perceptions (e.g. physical size, uniform strength across all subject areas and emotional robustness).

School administrators, teachers and parents may be reluctant to accelerate because of concerns about a student’s social and emotional maturity. It is important to consider the gifted student’s development and needs as part of any decision to accelerate; however the social and emotional characteristics associated with giftedness (especially sensitivity, intensity and the need to socialise with others at a similar developmental level) may be misinterpreted as emotional immaturity or social difficulties, especially by those unfamiliar with the traits of gifted students.

Social and emotional characteristics of gifted children:

Social and emotional characteristics of gifted children can be misinterpreted as emotional immaturity or social difficulties

Perhaps part of the difficulty with this intervention for high ability students lies around the use of the term “accelerate”. There is a tendency to think of this word in relation to driving a car. When the accelerator pedal is pushed, it makes the car go faster. Teachers and parents of gifted children (particularly those who are already concerned about being perceived as ‘pushy parents’) may regard academic acceleration as equivalent to pushing a child to move faster through school. Let’s be perfectly clear about this: academic acceleration does not involve pushing a child to go faster.

Academic acceleration does not involve pushing a child to go faster

Another way to think about acceleration is that the use of this educational strategy allows a student to make progress through school according to their own speed of learning, without being hindered. Academic acceleration effectively releases the brakes that age-based grouping imposes on gifted learners. It was this paradigm shift regarding academic acceleration that influenced the choice of the title for the research report about Australian acceleration practices, “Releasing the Brakes for High-Ability Learners”.

Research that has examined acceleration is unequivocal: acceleration is a highly effective intervention strategy for gifted students. Acceleration is not the only way to provide for gifted students; nor is acceleration suitable for every gifted child; however acceleration should be included as one of the provisions available for gifted students.

Make a Twist: Curriculum Differentiation for Gifted Students is a resource book full of ideas, strategies, and higher-order thinking challenges to engage high-ability learners. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Certain (free) e-Book readers are required to view the interactive e-book.

Any decision to accelerate a student should be based on sound evidence, made after careful consultation, with collaboration between home and school and always, with consideration for the needs of the student.

Consider if acceleration it is the best option for

– this student – at this time – in this context –

The research is clear: acceleration works. To ensure that a particular form of acceleration is the optimum way to meet a gifted student’s needs, it is important to consider if acceleration it is the best option for this student; at this time; in this context.

Emeritus Professor Miraca Gross, Director of the Gifted Education, Research Resource and Information Centre (GERRIC) at the University of New South Wales and co-author of reports mentioned here, maintains that when considering and implementing acceleration, we should ‘hasten slowly’. It is important not to delay in considering acceleration as an option for gifted students; however decisions about acceleration should be made with care and based upon sound knowledge about giftedness and the research about acceleration.

Decisions about acceleration should be made with care and based upon sound knowledge about giftedness and the research about acceleration.

Co-author of Releasing the Breaks for High-Ability Learners and of Make a Twist, Michele Juratowitch, provides professional advice, counselling and support for gifted children. For more support on the acceleration of gifted students, social and emotional support for gifted students, support in approaching a school about acceleration, professional development or advice, please get in touch with Michele Juratowitch, Clearing Skies.

References

Rogers, K. B. (1991). A best-evidence synthesis of the research on academic acceleration. Proceedings from the 1st Biennial Wallace Research Symposium for Talent Development. New York: Trillium Press.

Rogers, K. B. (2002). A research synthesis of “best practices” in gifted education: What does the research say? Keynote presentation for the 5th Biennial Wallace Research Symposium for Talent Development. Iowa City. IA.

Rogers, K. B. (2004). Academic effects of acceleration. In N. Colangelo, S.G. Assouline and M. Gross (Eds). A nation deceived how schools hold back America’s brightest students: The Templeton National Report on Acceleration. Volume II. (pp 47-57). Iowa City: Belin Blank International Centre for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Lubinski, D. (2004). Long-term effects of educational acceleration. In N. Colangelo, S.G. Assouline and M. Gross (Eds). A nation deceived how schools hold back America’s brightest students: The Templeton National Report on Acceleration. Volume II. (pp 23-37). Iowa City: Belin Blank International Centre for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Brodi, L. E., Muratori, J. C. & Stanley, J. C. (2004). Early entrance to college: Academic, social, and emotional considerations. In N. Colangelo, S.G. Assouline and M. Gross (Eds). A nation deceived how schools hold back America’s brightest students: The Templeton National Report on Acceleration. Volume II. (pp 97-107). Iowa City: Belin Blank International Centre for Gifted Education and Talent Development.

Book gifted | authors: Juratowitch, M. & Blundell, R.

Make a Twist eBook and hardcover book make the education of gifted students practical and accessible!

FIND OUT MORE

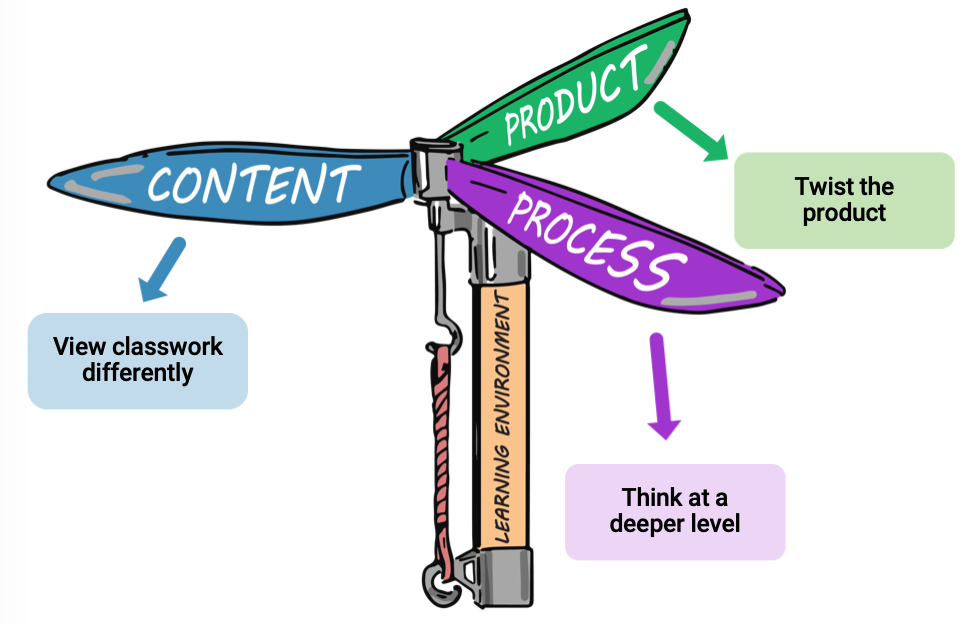

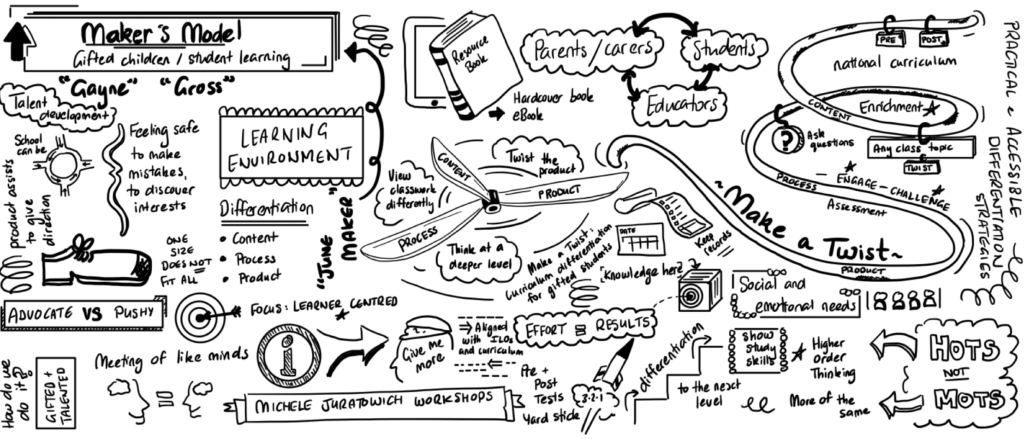

Make a Twist is a book that puts educational theory into practice, assisting educators and parents to identify and implement appropriate differentiation strategies for gifted children. Activities, aka ‘Twists’ contained in the book, are readily aligned with all subjects, curriculum topics, assessment tasks, and student interests.

The book is designed for upper primary school to middle high school high-ability students. The book can be used for higher-order thinking challenges during lessons and for extended differentiation tasks.

The gifted education book puts into action the principles of June Maker’s curriculum modification strategies (the ‘Maker model’) in a way that is complex and challenging, appropriate and engaging for high-ability children.

Make a Twist is a wonderful, totally practical way to put the principles in the Maker model into action in a classroom.”

C. June Maker

Make a Twist is a book that guides educators to develop an understanding of a learner’s abilities, skills, strengths, interests, creativity, and learning needs. It facilitates evidence of the adjustments made in support of gifted students throughout their learning.

Make a Twist is the perfect tool and guide to enable action in all school gifted and talented programs

Make a Twist can be used for advocacy of gifted children’s learning needs. It can connect parents and educators by opening communication, presenting easy-to-use strategies and ideas for differentiating classroom practice and for supporting the learning of the high ability child.

Parents can gain insight into their gifted child’s learning and learning development, the book also a recommended addition to support homeschooling of high ability children.

A resource book full of ideas, strategies and higher-order thinking challenges to engage high ability learners. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Certain (free) e-Book readers are required to view the interactive e-book.

Book gifted | authors: Juratowitch, M. & Blundell, R.

Make a Twist helps the busy teacher take any class topic and make it suitable for gifted learners. When you just don’t have the time or the headspace, Make a Twist is at hand to support.

Pop in the class topic or the student’s choice of topic and the ‘Twist’ is ready to go! You’ll find that this book can be used for extension in every lesson as well as for extended differentiation tasks. Make a Twist is readily aligned to curriculum, assessment and current class work.

FIND OUT MORE

This book is an excellent resource to guide you and the class teacher to identify and implement enrichment work in the classroom or in the homeschooling setting that is appropriate and engaging for your child.

Make a Twist can open communication and enable parents to connect with the busy teacher; by offering a practical means for differentiation of the class content, assessment and school curriculum.

FIND OUT MORE Need more challenge and less boring ‘busy work’? Use class time to ‘make a twist’:

Need more challenge and less boring ‘busy work’? Use class time to ‘make a twist’:

Make a Twist is a great addition to all gifted and talented programs

Make a Twist is used by educators, parents/carers, and students across the world!

In this article:

Supporting gifted children in the classroom

When given an opportunity to explore an area of interest, gifted kids produce extraordinary work. Sometimes the work and creativity produced by students is at the level of experts and professionals. Innovative ideas, valuable research studies, practical solutions for problems in society and breathtakingly creative works have been developed by gifted and talented students.

To perform at an expert level requires considerable intellectual abilities, deep knowledge, creativity, specific skills and a willingness to take realistic risks. Students preparing passion projects have an opportunity to demonstrate expert performance in an area of personal interest and relevance.

Gifted children require sufficient stimulation to focus their attention; higher levels of challenge to personally engage with new material; an understanding of their emotional sensitivities and psychosocial needs to structure a learning environment that provides a nurturing, supportive climate to ignite learning.

Gifted kids require:

Make a Twist eBook and hardcover book make the education of gifted students practical and accessible. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Certain (free) e-Book readers are required to view the interactive e-book.

Book gifted | authors: Juratowitch, M. & Blundell, R.

Make a Twist is a resource book full of ideas, strategies and higher-order thinking challenges to engage high ability learners. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Maureen Neihart has identified seven mental competencies (similar across different domains) and the factors that facilitate expert and gifted children’s performance.

Seven mental competencies and factors that support performance

In this context, risk refers to feelings of doubt that the goal can be achieved; to understand that new skills must be developed to accomplish the task. As Neihart describes,

a willingness to work at the edge of competence.”

Maureen Neihart

This is frequently accompanied by uncertainty and the feeling of teetering at the edge of the safe, known world; unsure about what lies ahead; realizing courage and persistence are required to move forwards to success.

To accomplish challenging tasks, it’s important to have a vision of what might be accomplished. There is a need to: establish the goals – both large and small; identify the skills required; develop the skills; allocate sufficient time; work hard in productive ways; manage feelings of uncertainty or fears and make steady, determined progress.

Understanding at the outset that challenges and difficulties lie ahead is part of mentally preparing for the work. Building in regular stress reduction techniques, including study breaks, exercise, relaxing (but not distracting) activities and time with friends can help to ensure that anxiety and mood are managed. Identifying who can provide practical help for the work and emotional support along the way is an important way of acknowledging and anticipating that there will be hurdles to overcome.

Knowing that others are travelling along a similar route can be helpful. Planning ways to collaborate, share strategies and work alongside friends can be ways of managing the need to belong to a group, together with the need to achieve.

Geoff Masters, CEO of the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER), recently referred to the importance of maximizing students’ learning by incorporating the work of American psychologist, David Ausubel and Soviet psychologist, Lev Vygotsky, whose work, Masters claimed, identified:

… the way to maximize learning is to stretch or challenge learners in a way that is appropriate to the points they have reached in their learning.”

Geoff Masters

This is aligned with Mihaly Csíkszentmihályi’s Flow concept and author Jane Piirto’s powerful statement:

Nothing inspires smart people so much as intellectual challenge.”

Jane Piirto

It’s critical for positive identity formation to focus upon children’s strengths. Csíkszentmihályi refers to the importance of focusing upon personal strengths and Masters emphasizes the importance of stretching and challenging children when he states:

If teachers are to provide all students in a class with learning experiences that will stretch and challenge them, they must be able to differentiate their teaching to meet the needs of students who are at quite different points in their long-term progress.”

Geoff Masters

The educational resource book, Make a Twist: Curriculum differentiation for gifted students opens opportunities for intellectual challenge, for student to develop deep knowledge, to stretch their skills and experience risk an appropriate level.

Make a Twist: Curriculum Differentiation for Gifted Students is a resource book full of ideas, strategies, and higher-order thinking challenges to engage high ability learners. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Certain (free) e-Book readers are required to view the interactive e-book.

Book gifted | authors: Juratowitch, M. & Blundell, R.

Achieving at expert level in any area entails risk-taking, being willing to increase challenge and push the boundaries of one’s knowledge. It involves wanting to learn new information, develop new skills and explore possibilities. Being on the edge can be exciting, challenging and at times uncomfortable. It’s important for learners to build the psychological skills necessary for attaining excellence.

Parenting gifted kids and supporting their schooling

Parents might advocate for gifted children as they start school, a different class or a new school. Educators may not otherwise be aware that a child is gifted. From an early age, gifted children begin to mask abilities to fit in. It’s important for parents to provide the school and teacher with information about a child’s abilities, interests and achievements. This is especially important when a child is reading young, prior to starting school. It’s important for parents to acknowledge support for their child’s learning needs and to communicate any concerns, while they are young.

Parents can be effective when they join a parent association; make practical contributions; establish a positive presence in the school. This will hold parents in good stead if they later need to advocate for provisions for gifted learners. A gifted child may need a range of adjustments to learn appropriately at school and at home.

Organizations and associations supporting gifted kids:

Australia

The Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented (AAEGT) is committed to furthering the education of gifted and talented students across Australia. AAEGT members are parents, educators, academics/researchers and other professionals whose family or work life brings them in contact with gifted children. The AAEGT is home to the official peer-reviewed Australasian Journal of Gifted Education.

Canada

MENSA Canada lists a great wealth of parent resources, policies and organization relating to gifted education in Canada.

UK

Potential Plus UK supports children with high learning potential, their families and schools.

USA

The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC) supports those who enhance the growth and development of gifted and talented children through education, advocacy, community building, and research. The organization help parents and families, K-12 education professionals including support service personnel, and members of the research and higher education community who work to help gifted and talented children.

There are times when a task is ideally matched to a child’s intellectual abilities, academic and practical skills, passions, and needs. When a task is not too hard, not too easy but ‘just right’, a student will be engaged in learning. Educators can address the learning needs of gifted learners by differentiating the curriculum and implementing specific teaching strategies. Academic work should provide sufficient challenge for the child, requiring the student to stretch a little beyond the current level, so new learning takes place and academic skills are developed. The way in which a child’s strengths, abilities and gifts are identified, challenged and nurtured by parents and educators will largely determine whether a child develops skills and talents.

Make a Twist: Curriculum differentiation for gifted children can open communication and a connection with the busy teacher by offering a means for practical differentiated learning.

The book supports

Make a Twist a resource book full of ideas, strategies and higher-order thinking challenges to engage high ability learners. Learn more about the hardcover book and e-book here.

Certain (free) e-Book readers are required to view the interactive e-book.

Book gifted | authors: Juratowitch, M. & Blundell, R.

Gifted children, require sufficient stimulation to focus their attention; higher levels of challenge to personally engage with new material; an understanding of their emotional sensitivities and psychosocial needs in order to structure a learning environment that provides a nurturing, supportive climate to ignite learning.

Michele Juratowitch, author of Make a Twist, is Director of Clearing Skies and provides a range of services to meet the needs of gifted children, their parents and teachers. Michele has qualifications in counselling, mental health and gifted education and provides counselling, social and emotional support for gifted children and their families. She worked in schools for over twenty years and has instituted a range of programs and provisions for gifted students.

Authors of Make a Twist | Book gifted

Michele has qualifications in counselling, mental health and gifted education and provides counselling for gifted youth and their families. She is Director of Clearing Skies and provides a range of services to meet the needs of gifted children, their parents and teachers. She worked in schools for over twenty years and has instituted a range of programs and provisions for gifted students.

Michele develops resources; provides training for teachers and parents of gifted children; lectured in the postgraduate course in Gifted Education at the Gifted Education Research, Resource and Information Centre (GERRIC) at UNSW; is a consultant to schools and member of advisory committees.

Michele regularly presents at national conferences, offers tailored educator professional development, and parent support workshops.

Michele has recently published a series of eBooks Raising Bright Sparks, supporting gifted students to achieve their academic potential.

Rosanne’s expertise comes not only from the classroom and across the STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) teaching areas, but from the training of teachers at a tertiary level. Rosanne has a particular passion for implementing effective strategies for the education of gifted and talented children, converting theory into practice. She has played an active role in the Queensland Association for Gifted & Talented (QAGTC) association; running workshops, supporting parents and teachers; and presenting.

Rosanne designs and develops teaching resources and eLearning for schools and industry under various University of Queensland and University of Tasmania partnerships to improve their educational resources. She is highly experienced in middle-years education, problem-based and inquiry learning both nationally (Australia) and Internationally.

Rosanne is also the creator of AR by Teachers which brings augmented reality learning Apps to the classroom.

The Australian Association for the Education of the Gifted and Talented (AAEGT) has declared that the third week in March will be the annual National Gifted Awareness Week. Raising awareness about gifted students and their needs prompts an examination of some of the myths associated with giftedness.

Miraca Gross, Director of GERRIC at the University of NSW has explained: all children are a gift; all children have relative strengths and weaknesses; however not all children are gifted because the term ‘gifted’ is a psychological and educational term and refers to the top ten percent of the population in any field. All children are unique and each child is valued. Gifted Education isn’t about valuing some students more than others; it is simply related to identification of intellectual and learning differences and meeting a student’s associated educational needs.

Gifted education is related to the identification of intellectual and learning differences and meeting children’s associated educational needs.

Gifted students are not all the same or evenly developed. Birthday gifts are varied, with some neatly boxed, beautifully wrapped, while others are presented haphazardly, with parts protruding beyond plain paper, barely held together with sticky tape. So it is with the gifted. Some students appear to be ‘evenly packaged’ whereas others are existing in an uneven, disorganised state.

Asynchronous development refers to the unevenness often found in gifted students’ profiles. A gifted student may be at a certain chronological age, but simultaneously at different levels in their physical, intellectual, social and emotional development. There can be marked discrepancies between various abilities and/or when these are compared with specific skills.

Asynchronous development refers to the unevenness often found in gifted students’ profiles.

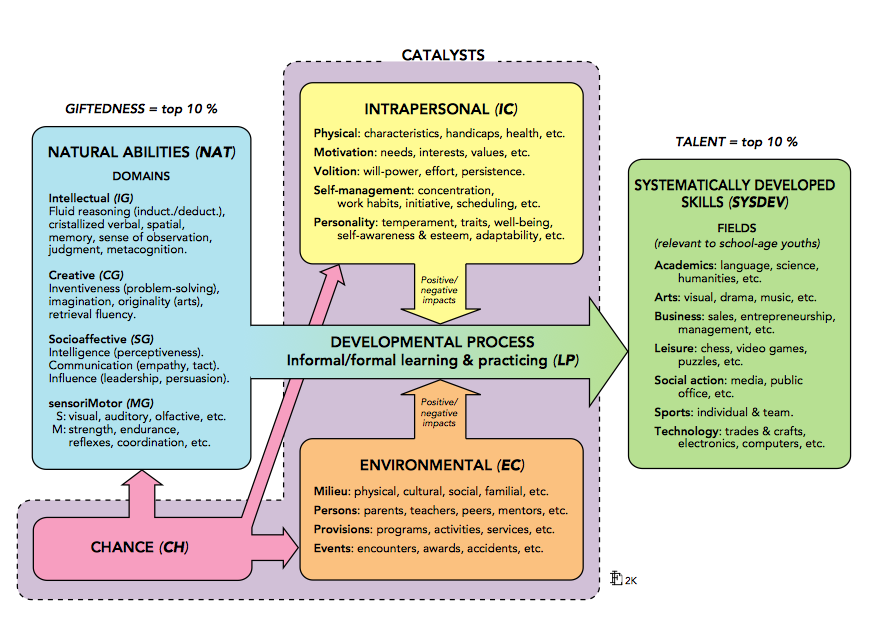

Heightened abilities can co-exist with relative deficits in skill areas that have not yet developed. Françoys Gagné, from the University of Quebec, explains that gifts or natural abilities will, in a stimulating and nurturing environment, progress to become systematically developed skills or talents, but this doesn’t necessarily occur in a smooth, even or linear manner. At another level, giftedness can co-exist with a range of disabilities, in physical (e.g. visual or hearing impairments) or cognitive (e.g. learning disabilities or attention) areas. These students are exceptional in two or more areas, have very complex needs and experience significant frustration.

Twice-exceptional, or 2e kids are exceptional in two or more areas. They have very complex needs and experience significant frustration.

There is no doubt that Stephen Hawking has an extreme physical disability coupled with an extraordinary, brilliant mind; however there are numerous ‘twice-exceptional’ students who have concurrent advanced abilities and disabilities but their complex needs may not be easily identified or adequately supported within an educational context.

Two bi-partisan Senate Select Committees have identified that gifted students are the most educationally disadvantaged population in this country. Gifted students require identification, understanding and appropriate educational provisions in order for them to develop talents and achieve at a level appropriate to individual potential. Without targeted provisions and relevant support at home and at school, gifted students risk academic underachievement, personal and social difficulties.

Gifted students are the most educationally disadvantaged population in Australia.

Schools are increasingly aware that addressing the needs of gifted students is related to educational equity and that school retention, academic achievement, social inclusion and personal well-being depend upon teachers’ awareness and professional skills to address the needs of gifted students.

© Michele Juratowitch

michele@clearingskies.com.au

Everyone has relative strengths, but children whose abilities fall within the top ten percent of the population in any area are regarded as ‘gifted’, according to Françoys Gagné, Emeritus Professor of Educational Psychology at the University of Montreal. Michael Pyryt,from the University of Calgary, described the difference between strengths and giftedness as similar to weaknesses and handicaps, saying:

We all have weaknesses but we don’t all have handicaps.”

Miraca Gross, Emeritus Professor and Director of the Gifted Education Research, Resource and Information Centre (GERRIC), at the University of New South Wales, said:

Every child is a gift; every child, irrespective of ability levels has relative strengths and weaknesses; but not every child is gifted.”

The term ‘gifted’ is a psychological and educational term.

Gagné explains a developmental process is required to transform a child’s natural abilities or ‘gifts’ (when occurring in the top 10% of the population), into systematically developed skills or ‘talents’ (when occurring in the top 10% of the population).

Image source: https://www.curriculumsupport.education.nsw.gov.au/policies/gats/assets/pdf/poldmgtcolrdiag.pdf

A child can be gifted without being talented (because their talents have not yet developed); however an individual cannot be talented without first being gifted. There are a range of factors that impact positively or negatively upon the developmental process, reaching one’s potential and talent. A child may have a natural ability, but if she or he does not enjoy the activity, lacks motivation and does not put in sufficient effort, this ability is unlikely to develop into a talent. Gagné highlights the impact of people, resources, events and opportunities in a child’s life in developing potential. The development of talent depends on what the family, school, culture and the child contribute.

The development of talent is influenced by factors such as:

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. These cookies ensure basic functionalities and security features of the website, anonymously.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

Functional cookies help to perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collect feedbacks, and other third-party features.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with relevant ads and marketing campaigns. These cookies track visitors across websites and collect information to provide customized ads.

Other uncategorized cookies are those that are being analyzed and have not been classified into a category as yet.